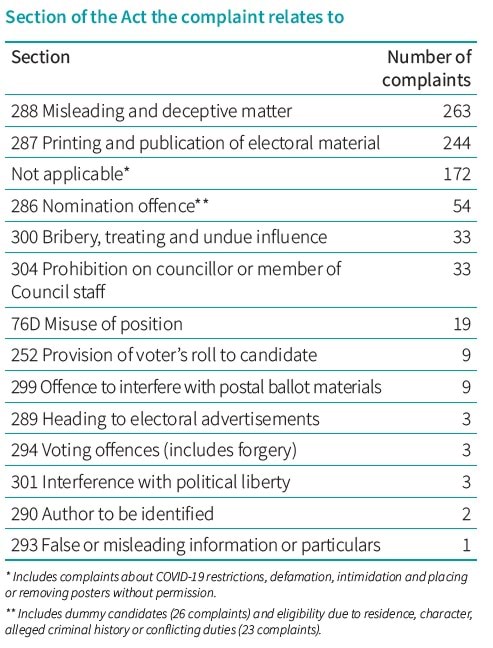

When assessing complaints, we look at whether or not there has been a breach of the Act and what section of the Act has been breached. We receive the most complaints about things that related to authorisation of election material and misleading and deceptive conduct.

Most common breaches or offences we received complaints about

The Act requires election material to be authorised for transparency. Authorising information allows the electorate to see the name and address of the person publishing the election material, which also makes that person accountable for claims or commitments made on that material.

In 2020, 244 complaints related to alleged failures to comply with the election material authorisation provisions of the Act, which require the authoriser’s name and address to appear at the end of the material. The intent of this requirement is to allow voters to access the source of the information and allow an opportunity to question representations made.

The majority of these complaints related to the absence of any authoriser’s details, however, other issues were also raised. Complainants also questioned the content and validity of authorisations. We received allegations that the author was not an actual person and that the addresses given were not valid.

Following our initial enquiries, we found that in 152 of the cases, an offence was substantiated and, in most cases, compliance was requested and achieved. Given the low-risk nature, we determined that it was not in the public interest to further investigate for the purpose of prosecution. Greater value was placed on providing guidance and educational material. In 129 cases, formal warnings for the offences were issued.

In 2016, there were 122 complaints about authorisation of election material compared to 244 in 2020, meaning there was a 100 per cent rise in authorisation complaints between 2016 and 2020. This may be a result of the changes in technology and the rise of candidates increasingly using social media channels to run campaign and influence the community’s vote during the election period.

Social media, its impact, and whether the current legislation takes the changes in technology into consideration, will be discussed later in this report.4

4. See Rise of social media complaints, Sexism, bullying, harassment and social media; and Social media.

More than 260 complaints were made about misleading or deceptive electoral matter during the elections. Many complaints disputed the accuracy of statements made by other parties in material published either by themselves, or other candidates.

Section 288 of the Act states that a person must not print, publish or distribute any matter that contain a representation of a ballot-paper to be used in an election that is likely to mislead or deceive a voter in the casting of their vote. This includes the printing, publishing and distributing of electoral advertisements, handbills, pamphlets or notices.

In 2016, we received a large number of complaints about misleading and deceptive matter and conducted investigation work as a result. In our report on the 2016 elections, we noted that there was a gap between the expectations set by the legislation and the reality of how it is interpreted by the legal system.

In most cases, complainants believe that any statement that is not totally accurate constitutes an offence. However, the courts have ruled that statements may be considered misleading and deceptive because they lead the voter to mark the ballot paper in a way, other than correctly, and not to refer to untrue statements which may contribute to the formation of an opinion about a candidate.5

This continued to be an issue during the 2020 election and was exacerbated by the increasing impact of social media, where false claims could less easily be tested than in a traditional face-to-face public forum where untrue statements can be challenged and debated.

5. Evans v Crichton-Browne (1980) 147 CLR 169

Following an initial assessment by the Inspectorate and the VEC, Victoria Police investigated alleged ballot tampering in the Moreland Council election, a matter that was comprehensively covered by metropolitan media.6 During the investigation, we provided background advice on local government.

In March 2021, it was reported that fraud squad detectives had arrested a candidate who was elected in October 2021, and interviewed them in relation to the offence of making a false document.

6. The Age, ‘$500 for 50 ballots’: Police called in over Moreland vote tampering claim, published 3 November 2020, viewed 3 May 2021.

Updated