- Date:

- 21 June 2021

Once every four years, Victoria holds its general council elections. This is generally a vibrant time for local government in Victoria but the pandemic and the resulting restrictions on movement created unprecedented conditions.

As the dedicated integrity agency for councils, we oversight councils, councillors, candidates and voters pursuant to the electoral provisions of the Local Government Act 2020. Accordingly, the year leading up to the elections, and particularly the four-week election period, is a busy period for the Local Government Inspectorate.

In the 2020 election period, we received 848 complaints – a 107 per cent increase on 2016. There was an even split between the number of complaints made by members of the public and those made by candidates. Most complaints (78 per cent) were generated from 22 councils with 20 councils generating no complaints at all. Three councils did not hold elections because they were under administration.

Alongside the numbers, we saw trends and heard anecdotal evidence that the behaviour of a number of candidates went well beyond what might be considered robust political activity. Long-time councillors reported to us that this was the most toxic and vitriolic election that they had ever experienced. In addition, we saw numerous examples of unethical and underhand behaviour – but it was behaviour which did not breach any laws. This is a concerning trend that we will continue to monitor.

We believe there were two major factors behind the rise in complaints and the deterioration of decent behaviour by candidates and their supporters.

In October 2020, Melbourne was coming to the end of one of the world’s longest and toughest lockdowns at that point in time. The COVID-19 restrictions which were introduced to stop the spread of disease limited resident movement to just 5km from home for only two hours per day, apart from permitted workers. The lockdown heightened the anxiety of the electorate and provided perhaps another reason for people to file complaints against candidates for allegedly breaching restrictions.

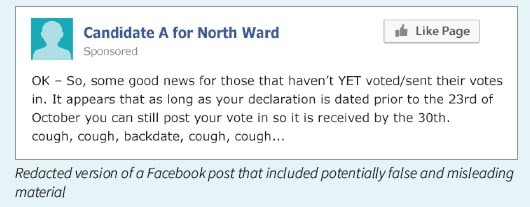

In addition, 2020 continued to see the rise in the dominance of social media. This was compounded by the collapse of local and regional newspapers during the year. Complaints about unfavourable interactions, false or misleading material or, at the extreme end, harassment and abuse on social media rose two and a half times (by 241 per cent) from 2016 figures. Social media is free and easy to use. Consequently, it is a very popular place to campaign – but regulation and limitations on content posting have been slow to occur. The ability for people to set up anonymous or unauthorised political accounts may have allowed some candidates or campaigners to post false, misleading or abusive material.

The new Local Government Act 2020 made some significant changes to the election process, such as introducing mandatory training for candidates. In this report, we have recommended further amendments to the legislation to rectify some ongoing election issues and to be authorised to issue penalty notices in lieu of pursuing potentially lengthy and costly prosecutions for minor infringements.

The 2020 elections were also the first occasion some complainants could use the protections under the Public Information Disclosure Act 2012. We worked with the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC) to ensure that investigations and the processing of complaints were not delayed by the new protections.

I am pleased to publish this report as an insight to the key integrity issues, challenges and outcomes for the 2020 general council elections in Victoria. As my role as Chief Municipal Inspector only began in April 2021, I need to acknowledge the significant work of Dr John Lynch as acting CMI and the Inspectorate team over the election period and throughout most of 2020.

I also want to acknowledge the partnership with the Victorian Electoral Commission (VEC) and integrity agencies in receiving and referring complaints in a timely manner, and the hard work of legitimate candidates in campaigning during a challenging year.

Michael Stefanovic AM

Chief Municipal Inspector

June 2021

Introduction

Victoria held its local government elections in October 2020, attracting 81 per cent of voters to cast a ballot – the highest ever average turnout for local council elections. The elections were a ‘win for democracy’ with a low level of informal votes from the 4.29 million voters – the highest number enrolled for an electoral event. October 2020 also saw the largest number of candidates for an electoral event with 2,187 candidates nominating to stand for election at their council.1 However, the celebration of participation hid some concerning trends.

The Local Government Inspectorate, the lead integrity agency for Victorian local government, has observed trends in the sector for more than a decade. During the 2020 election, we spoke to councillors - some with up to 16 years’ experience in the role - who said the 2020 election was the most vindictive and vitriolic election they had participated in.

“I’ve never seen such toxic behaviour in any other election”

– Former councillor who did not stand for re-election

Once councillors are elected, they receive the Schedule to the Local Government (Governance and Integrity) Regulations 2020 which tells them how they are expected to behave. However, candidates, during the election period, often consider any type of behaviour is acceptable as long as it is legal.

In 2020, we saw a 107 per cent rise in the number of complaints compared to 2016. In the first few weeks of the election period, we had low numbers of complaints. However, about 10 days before the ballots closed, there was a significant increase in the volume of complaints and our team worked effectively and efficiently to analyse complaints and assign them to investigators if required.

The 2020 elections took place during an unprecedented worldwide pandemic and Melbourne enduring lockdowns that limited election candidates to mainly online and limited campaigning in public.

“A state of disaster has been declared, we are juggling working from home, home schooling, help[ing] our families cope with their mental health, helping friends, extended families [and] people in the community. Add on the extra task of organising your campaign for the elections and you are lucky to have your head intact at the end of the day.”

– Submission by an election candidate to the Parliamentary Inquiry into the Impact of social media on elections and electoral administration

“It was a COVID election. Candidates were not able to get out and meet the public.

“One councillor was elected but the public didn’t actually get to see or hear them. They were elected on written material which was written by the ratepayers association. There have been a lot of questions about how this councillor got elected to represent the community.

“It is hard to get good candidates to run. I know there were a couple of really good candidates but they didn’t run. It was too hard because of COVID.”

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

With in-person campaigning mostly impossible, the majority of candidates had an active social media presence. Social media is a low-cost way to reach a lot of people and this trend was exacerbated by the COVID-19 restrictions and the closure of many local newspapers. We saw a 241 per cent increase in social media complaints in the 2020 election period in contrast to the 2016 elections.

In 2020, there was also a rise in the number of candidates lodging complaints against each other, with the most disturbing of these being the ‘weaponising’ of our complaints process. This often involved a candidate submitting a complaint and then attempting to publicise their actions through traditional or social media, to cast aspersions on a rival candidate.

“A large number of my posts of Facebook were targeted by a councillor who was running for re-election in a different ward. This councillor would say that I was wrong, they would accuse me on lying and they would threaten to report me to the Local Government Inspectorate.”

– Councillor elected for the first time in 2020

Many of those ‘weaponised’ complaints related to incorrect or missing authorisations of electoral material, particularly on candidate’s social media pages or accounts. Later in this report, we recommend amending section 287 of the Local Government Act 2020 to clarify the definition of electoral material to in relation to online material, and clarify the areas where electoral authorisations are required for transparency.2 During the 2020 election period, considerable time was spent in intervening in disagreements between candidates and advising complainants who did not understand the laws that govern the election period, despite the guidelines and training material provided by the VEC.

We also continue to see a misunderstanding of the scope and application of section 288 in relation to misleading and deceptive conduct.3

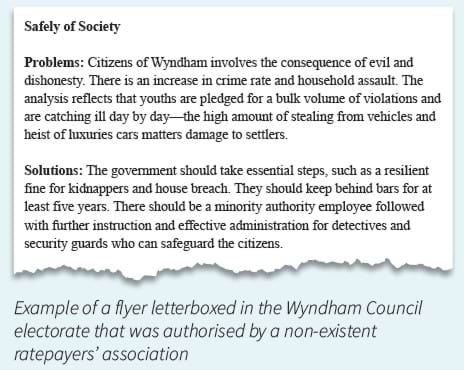

We also noted an increase in activity from community and ratepayer groups. We received complaints about the actions of ratepayer groups and received complaints from ratepayer groups. Community and ratepayer groups had significant input into the election, and they must understand that they are governed by the same legislation as candidates.

“I am a long-time councillor and this year is the first time I have ever thought about quitting. My family has been attacked by other candidates. It happened during the election period and has continued.”

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

Meanwhile, transparency and integrity on matters, such as electoral donations, was in the spotlight in 2020 because IBAC held public hearings relating to allegations of serious corrupt conduct in planning and property development decisions at the City of Casey.

Current legislation requires all council election candidates to submit a campaign donation return, which is a record of gifts or in-kind support, received by candidates for use in their campaigns. In 2020, the number of candidates who had failed to comply with this law halved, dropping from 13 per cent in 2016 to six per cent last year. There were four candidates who failed to submit a campaign donation return in both 2016 and 2020.

More information about penalties for electoral breaches is included in Appendix 1.

1 Victorian Electoral Commission, 2020, A win for democracy in a challenging year, Victorian Electoral Commission, viewed 3 May 2021

2 Section 287 is listed in full in Appendix 2.

3 Section 288 is listed in full in Appendix 2.

Our role in the 2020 elections

The Local Government Inspectorate is the leading integrity agency for Victorian councils.

We work with other government agencies help ensure a fair and democratic election process. Our responsibilities include:

- candidate eligibility

- advice to and monitoring the conduct of councils and candidates

- and assessing allegations

- investigations into potential offences under the Local Government Act (1989 and 2020 Acts).

The council election period starts on the last day nominations are accepted by the VEC and ends at 6pm on election day. The 2020 election period started on 22 September and ended at 6pm on Saturday 24 October.

However, our role in council elections started more than a year before election day and continued long after the closure of the official election period.

Electoral provisions are set out under Part 8 of the Local Government Act, which commenced on 6 April 2020, but some relevant provisions commenced on election day, 24 October 2020.

The complaints process

Elections in Australia allow for robust political debate and the expression of opinion. It is vital that complaints are received, assessed and dealt with swiftly to ensure fair and transparent elections. A swift process also reduces the opportunity for the complaints process to be manipulated and used as a campaign tool.

It is critical that substantive matters, that carry a risk to the system, are identified and appropriately investigated to determine the best outcome in consideration of the public interest. However, it is also important to quickly deal with complaints that are without basis, not in good faith and are low-risk offences caused by a lack of understanding, or a genuine mistake.

Case study

Impact of the new Local Government Act

The Local Government Act 2020 (2020 Act) delivered a range of changes to improve the transparency and accountability of local government, including electoral reforms.

Part 8 of the 2020 Act deals with local government elections and draws on reform proposals aimed at improving the democratic legitimacy of councils by:

- creating simpler and more consistent electoral structures

- modernising the council franchise and councillor qualifications.

Part 8 is the largest Part of the 2020 Act consisting of 11 divisions (including electoral offences) and 87 sections. It substantially reformed the local government election system contained in Part 3 of the Local Government Act 1989 (1989 Act).

While the 2020 Act aims to improve the local government election process, we want to see a number of amendments to further improve transparency and strengthen the role of the CMI to regulate the sector during the election period.

Elections complaints data and themes

During the 2020 election period, we received 848 complaints. This was a 107 per cent increase on complaints in relation to the 2016 election period. During the 32 days of the election period, our staff handled, on average, 36 complaints per day.

The Inspectorate is a complaints-based agency. It is important that members of the community know which agency to lodge a complaint to and seek advice from, as well as what constitutes a valid complaint. The rise in enquiries and formal complaints shows us that the community feels comfortable raising issues and is aware of our role.

In a non-election year, we receive and address an average of 500 formal complaints a year. In the election period, this number increases substantially.

Those who contact us for guidance, information, or to lodge a complaint had varying degrees of involvement in the election and included councils, councillors, candidates, and voters.

Although not all complaints received related to an offence under the Act, each interaction was an opportunity for us to gain insights into emerging issues, identify trends and areas where education or legislation reform could contribute to higher levels of accountability and transparency at councils in Victoria.

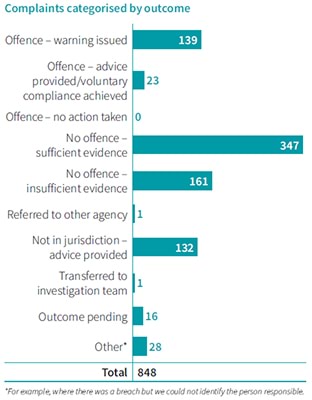

The graph below shows the breakdown of complaint outcomes. Note that several matters are still under review and may progress to investigations.

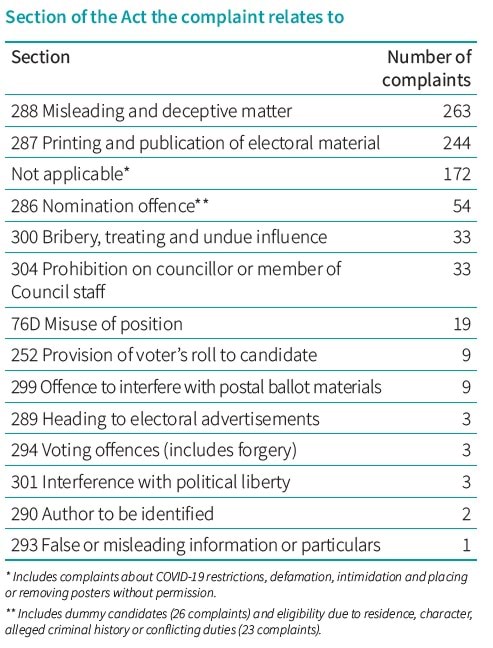

In comparison to the 2016 election period, there was a substantial increase in complaint numbers. In 2020, complaints about misleading or deceptive matter made up about 31 per cent of the complaints and complaints about printing and publication of electoral matter made up 29 per cent of complaints. These two categories comprised 60 per cent of the total number of complaints.

Our performance

During our assessment process, we:

- identify complaints that have no foundation

- provide advice or warnings for low-level matters

- escalate matters, that present a risk of serious offence or to the electoral system, for further investigation.

Between 31 August and 8 November, our election complaint form was accessed 922 times, peaking in the week of 5–11 October when 209 sessions were recorded. Our ‘Make a complaint’ page was viewed 1621 times in the same period.

Our office was affected by the State of Emergency which operated in Victoria for most of 2020. For extended periods, Victorians were directed to work from home, where possible, avoid gathering in groups and limit travel. As a result, we had to find new ways to continue to prepare and operate during the local government election period. However, the change in working arrangements caused issues.

From 2–9 October 2020, our office was affected by a telecommunication failure of our main landline numbers and this took longer than expected to resolve due to phone provider issues and the COVID-19 restrictions on movement.

As a result of this failure, we were not able to determine the exact number of complainants whose calls when unanswered during this time. However, complainants were able to contact us through other means such as our online complaint form, email and referrals from other agencies, and advice was provided on our website to indicate preferred methods of contact.

Where we received complaints from

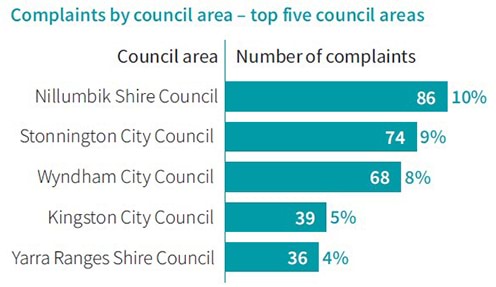

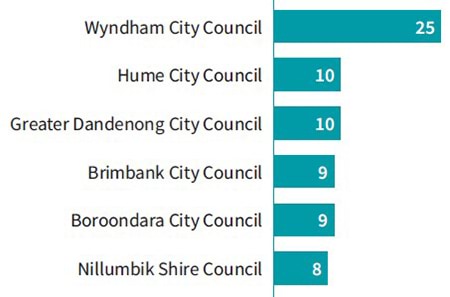

Of Victoria’s 79 councils, we received no complaints about 20 councils (including three under administration where there were no elections) and received 10 or less complaints per council about 37 councils. This meant the vast majority of complaints (78 per cent) related to just 22 councils. Furthermore, 228 complaints – a quarter of all complaints – related to just three councils: Nillumbik, Stonnington and Wyndham.

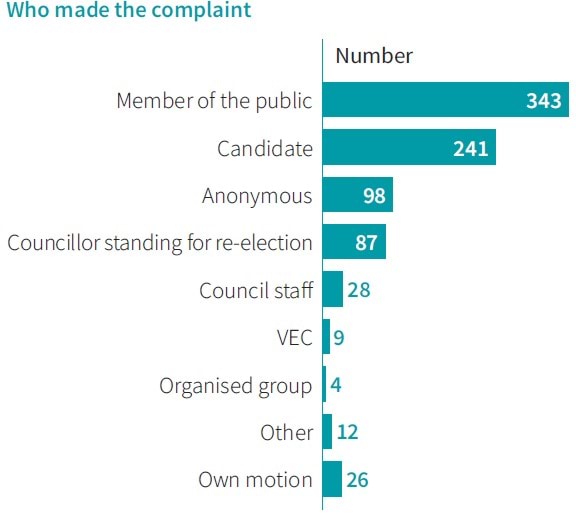

Who made the complaints

The majority of complaints were lodged by a member of the public with the second highest number lodged by candidates, including councillors standing for re-election. About 13 per cent were anonymous.

Case study

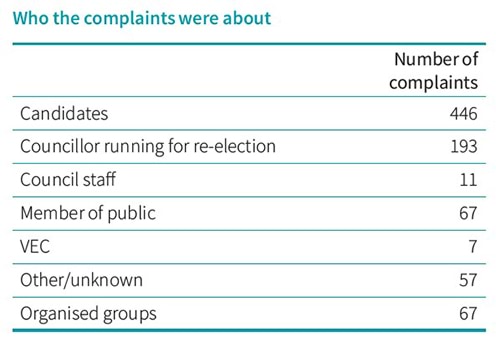

Who and what the complaints were about

Who the complaints were about

The majority of complaints were about candidates (53 per cent) with complaints about councillors running for re-election coming in second (23 per cent). This was an increase in the number of candidate-on-candidate complaints in 2016. The 2020 elections also saw a rise in complaints about organised groups, such as ratepayer associations and community groups (8 per cent).

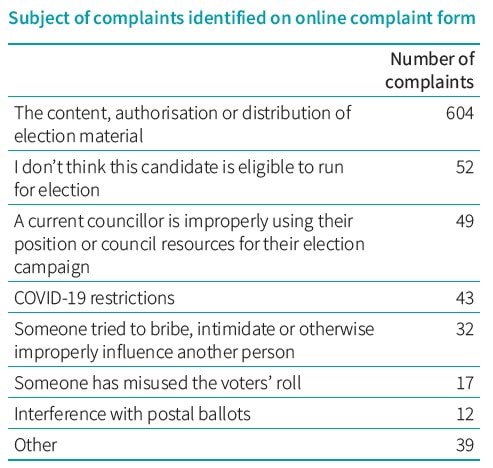

What the complaints were about

On our online complaint form, we asked for complainants to choose from a list of topics that best suited their complaint. The overwhelming majority of complaints related to the content, authorisation or distribution of election material.

Breaches and offences under the Act

When assessing complaints, we look at whether or not there has been a breach of the Act and what section of the Act has been breached. We receive the most complaints about things that related to authorisation of election material and misleading and deceptive conduct.

Most common breaches or offences we received complaints about

Rise of social media complaints

In 2020, complaints about the use of social media and online content in election campaigns more than tripled, from 78 in 2016 to 266 in last year. We received an increase of 118 per cent of complaints about the authorisation of election material during the 2020 election period and 31 per cent of all issues raised were about content that was specifically published online.

These figures show that social media’s impact has continued to grow since the 2016 elections. The rise of social media as a key campaign tool was exacerbated by the closure of many local papers during 2020.7 While social media provides an economical way for candidates with limited financial backing to reach the electorate, it can produce challenges for existing legislation.

The current legislation does not cater for the fast and fluid social and new media forums. We received many enquiries in relation to Twitter and whether tweets constituted election material that was required to be authorised. We received enquiries about the same issues arising around Facebook and received several formal complaints about the use of group emails. With the continuing dominance of the social media, we support a review of the current laws and how they operate in the new media landscape, or a tailored legislative approach for social media uses.

7. See Traditional media.

Case study

Pre-election work - what we achieved

Typically, election preparations will begin 12 months before an election period. The work we undertook during 2020 included:

- a Memorandum of Understanding with the VEC

- policies and processes for receiving and assessing complaints efficiently

- communication strategies and material to promote understanding about our role in election matters.

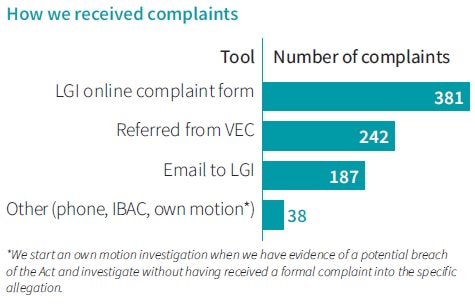

We developed an online election complaint form in August 2020 with comprehensive user testing and plain English wording to ensure complainants could understand what we could and could not receive complaints about.

There were 381 complaints or enquiries lodged through the specific election complaint form during the election period. Other complaints related to electoral matters were also lodged through the standard online complaint form and other methods such as phone calls and email.

We are also aware of and appreciate the work councils and the VEC do in handling potential complaints that are resolved before reaching our office. The VEC received enquiries and complaints and was able to resolve low-level enquiries before they were referred to us.

However, we were sent examples of election managers who had given candidates inconsistent or conflicting information.

We will continue to work with the VEC to ensure messaging for candidates is clear and consistent in the future.

Anecdotal evidence indicated that many councils received enquiries from staff, councillors and local residents about potential breaches of the electoral provisions and resolved many of them during the election period.

Election period policies

All Victorian councils must have a policy covering the election period, also known as the ‘caretaker period’. The election period policies ensure councils are transparent and accountable during the election process. The policy outlines how they will:

- fairness

- misuse of council resources

- inappropriate decision making.

“The caretaker policy causes angst amongst some councillors because they can’t represent the council at events during the four weeks before the election.”

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

To support councils, councillors and candidates to understand and meet the requirements of the Act, we produced a sector-wide Election Period Policy Report in 2016. The report included analysis of the review findings and clear guidance on:

- policies providing clear instructions stating that councillors are not to use appearances at public events for the purposes of electioneering

- policies stating that no electoral material is to be placed on council websites or social media during the election period

- including the election period policy in information packs provided to nominating candidates

- model policies from various other councils.

Our website also contains some best-practice examples of election period policies from a range of councils.

The new 2020 Act no longer requires the CEO to undertake a certification process, however councils are encouraged to cover in their election period policies how documents and other communications intended for release during the election period will be managed. This will ensure they comply with section 304 of the 2020 Act which makes it an offence to misuse resources to affect an election or intentionally produce election material during an election period.

The 2020 election period demonstrated that while councils have election policies prescribing that they should be apolitical and not comment on candidates and their platforms, there are instances in which they should be able to exercise discretion and correct misinformation circulating in the community.

Recommendation

1. Section 69 of Local Government Act should be amended to require councils to adopt a caretaker or election period policy, which:

- is based on the model election period policy prepared by LGV

- incorporates flexible election period policies which allows for misinformation to be corrected.

Case study

Candidate eligibility

In 2016, we completed a candidate eligibility review by auditing 10 per cent of the nominations and checking their criminal history. Of the 210 candidates we reviewed, we found two candidates that were ineligible to nominate and they were removed from their respective ballots.

However, in 2020, criminal history was only able to be obtained where there was reasonable evidence to indicate that a candidate had a criminal record. The short timeframe between the closure of the nomination period and the printing of the ballot papers means it is not viable to check all candidates for eligibility and intervene where required. The system relies on candidates understanding the eligibility criteria and then correctly completing the nomination form. The process is vulnerable to candidates misunderstanding the criteria or having an intention to deceive.

In line with the same arguments made in our 2016 elections report, we need to consider whether to place an extra burden on candidates who wish to nominate for elections to prove that they are eligible.8 This could be done by asking a candidate when they nominate for election to produce a police and bankruptcy check.

Council elections are held on a fixed date and known four years in advance, with the nomination period open for a five-day window just prior to the election period. Police and bankruptcy checks are valid for six months and can usually be obtained by a potential candidate within two days of application.

There is little risk that an eligible and genuine candidate would be prevented from nominating if this requirement was in place. In terms of the greater effort or additional hurdle that is required by the nominating candidate, that is a question of balance between the importance of the office of councillor and the steps required to nominate.

Recommendation

Regulation 24 of the Local Government Electoral Regulations should be amended to require candidates to provide a financial records check providing proof of no current or past bankruptcies, a police clearance certificate and a 100-point identification check when nominating for election.

8. See pages 14-15 of our report Protecting integrity: 2016 council elections

Candidate booklet

“I don’t know that I would want to campaign again as it wasn’t an enjoyable experience. It was full on and there was so much work and pressure. I was naive about what was involved and the implications for my family.”

– Councillor elected for the first time in 2020

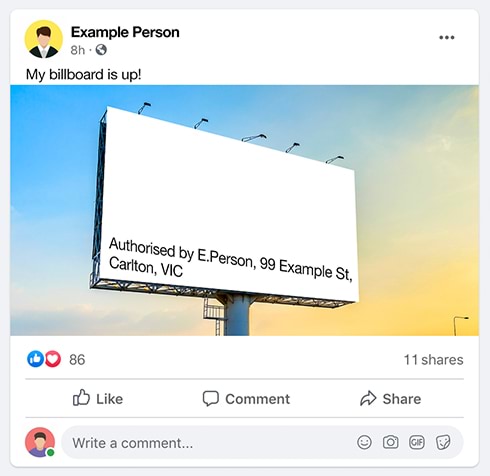

The VEC produced a handbook for candidates who intend to stand which covered nominating, election campaign material and election compliance. The 60-page booklet used in 2020 contains numerous sections from the Local Government Act 2020 with explanations of complex topics such as authorisation of electoral material and electoral offences.

There have been considerable efforts by the VEC to explain the election process simply but there is still room for improvement. During the 2020 local government elections, we found many candidates who contacted us had either not read or had not retained information from the candidate booklet.

Candidates come from a range of backgrounds, including different levels of education, community engagement and different cultural backgrounds. They may have a very basic understanding of democratic processes or come from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. The language and design of the booklet needs to be made as accessible as possible to be able to be understood by as many candidates as possible.

Simplifying the text and using other means of communication, such as images, video and infographics, could also help drive down the number of complaints or queries received by the VEC.

For example, the booklet should contain images and examples of authorisations for social media so that candidates can see exactly what they are expected to do when they post-election material on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

If candidates understand the rules and processes of the election process, there will be less confusion and less need to call the VEC to ask for advice and help.

Recommendation

Inspectorate will consult with the VEC and have input into the electoral candidate handbook to ensure candidates receive simple information about:

- the rules and laws candidates need to follow

- how election material should be authorised

- what constitutes a misleading or deceptive matter

- the Inspectorate’s role in electoral matters.

Candidate and campaigner behaviour

"The tactics we saw in 2020 will prevent good candidates from standing. We all want free and fair elections but I know good candidates who will not run again because of the tactics used. If you can see the way candidates are treated on social media then would you want to expose yourself by standing for election?"

Robust public debate is an accepted part of all levels of politics. While candidates must accept a certain level of questions and criticism during their campaign, there have been reported instances where candidates have been harassed online, followed or received death threats.

During the election period, we spoke to a number of long-term councillors who were contesting their third or fourth term. These experienced councillors reported that the 2020 election period was the most vindictive and vitriolic election they had participated in. We also received similar feedback from a local council which had spent a significant period of time dealing with complaints by candidates. This is a concerning trend and one we will monitor.

"Unless there is a series of standards for candidates, good honest community-based candidates will not run."

The election period is short and it is not always possible for us to receive and deal with complaints as quickly as complainants would like

A lot of the complaints we received were driven by a misunderstanding of the definition of ‘misleading and deceptive behaviour’. During a political debate, candidates can speak freely but unethical behaviour is not necessarily illegal.

“Our former mayor was very threatening. They would publicly accuse residents of lying on Facebook if they had a different view, accuse them of breaking the law and threaten to have them fined. When you have someone of high status in the community talking to people like that, it scares people and is not good for democracy.”

If we receive an allegation from a candidate about false electoral material that does not fit the definition of ‘misleading and deceptive’ in the legislation, we encouraged candidates to redirect their focus away from corresponding with us about the allegation and to concentrate on putting the issues to voters and continuing their campaign.

Many complaints focused on allegations of a breach of Section 287 of the Local Government Act 2020(opens in a new window), Printing and publication of electoral material (see Appendix 1) with the majority related to material published online. Because the wording in the Act does not specifically mention online or social media material, we joined the VEC in publishing information for candidates leading up to the election to advise them on the correct methods for authorising their campaign material on social media.

Recommendations

- Updating of the definition of ‘electoral material’ in section 3(1) to encompass social media and other forms of electronic communication.9

- Section 287 of the Act should be amended to incorporate social media and other forms of electronic communication.

9. Section 3(1) is listed in Appendix 1.

Case studies – Allegations of false or misleading material

Case study – Allegations of improper conduct

Sexism, harassment, bullying and social media

Sexism, harassment and bullying were again featured in the 2020 local government election period. Although we are not the primary body which would receive serious or criminal complaints of this nature10, we received 18 election complaints which mentioned harassment, threats or intimidation in 2020. A further 25 complaints mentioned defamation.

“I was accused of being a homophobe, corrupt and a dog killer. I had fringe radicals calling me a 3am and threatening to kill me. I didn’t call the police, I figure if someone was going to kill me then they were not going to tell me first. My wife also received a few death threats. It didn’t worry me, but it worried my wife and children.”

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

We observed that social media has fuelled harassment and bullying as it allows the behaviour to be done anonymously or by people using fake accounts. Comments in a closed Facebook group set up to advance female representation in Victorian councils, ‘More women for local government’, indicated that women candidates bear the brunt of bad behaviour.

A record number of women were elected to the October 2020 Victorian council elections in 2020 with 273 women elected, taking representation up to 43 per cent. However, research into the political careers of women in local government indicates that this may not be a cause for optimism. 11

“There was an information session about what it means to be a councillor but it didn’t really go into enough detail. I have found it difficult to juggle responsibilities for children with evening meetings.

“I am also aware that women are scrutinised more about what they wear and so I had to buy an entire new wardrobe. One of the male councillors wears the same suit to every meeting but there is a different expectation for female councillors.”

– Councillor elected for the first time in 2020

Our oversight role in council elections does not specifically look at gender but we will continue to observe the impact of sexism in local government elections. There are concerns that abuse and harassment online, particularly on social media, will dissuade women from standing for election.12

“Getting women elected as councillors is one thing – getting them to stay is another. The valuable skills and experience women gain after their first term is being lost because a lot of first-term women councillors don’t recontest and we need to understand why.”

– Former councillor who did not stand for re-election in 2020

9. Section 3 (1) is listed in Appendix 1

10. Serious or criminal complaints or harassment and bullying were referred to Victoria Police. Complaints of sexism were referred to the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission

11. Women in Local Government: Understanding their Political Trajectories, is a four year research project funded by the Australian Research Council by Leah Ruppanner (University of Melbourne), Andrea Carson (LaTrobe University) and Gosia Mikolajczak (University of Melbourne), in partnership with the Victorian Local Governance Association. The project surveyed 110 male and 125 female newly elected Victorian councillors. Of those, 44 per cent of women and 23 per cent of men had reported experiencing repeated condescending behaviours during the campaign period.

12. Gender Equity Victoria’s submission to the Victorian Parliamentary Inquiry into the Impacts of Social Media on Elections and Electoral Administration, viewed on 4 November 2020, stated that “gendered and identity-based cyberhate experienced by women politicians is a serious threat to our democracy”. The peak body for gender equity said that women were underrepresented in elected office in Victoria and British studies suggested online harassment and abuse makes it less likely women will stand for election.

Role of media in elections

This section discusses the changing role of traditional media on elections as social media has largely taken its place for candidates, supporters and voters.

The traditional media in the form of regional and community newspapers, and radio stations in many areas, have often played a key role in council elections. These outlets would profile local candidates, feature campaign advertising and umpire political debate between candidates and the community they serve.

Social media is popular as a cheap and easy way to broadcast campaign messaging. Increasingly, the public turns to social media as a ‘source of truth’ for news and information about politics.

Policing social media is problematic as the technology companies that run the platforms are based overseas and, until recent times, not subject to many Australian laws on content or publication of material. They have, so far, successfully argued that they are not publishers and therefore are not subject to defamation laws.

Traditional media

“Without a local paper there is very little scrutiny or oversight of candidates. The local paper had credibility and wasn’t a candidate pushing their own barrow like most election material. We do have a local paper but it is online and behind a subscription paywall, so people don’t read it. The stories have to pay for themselves and so the journalism is very superficial.”

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

Australia’s traditional and online media landscape has been changing for the last decade. However, this change was supercharged in 2020. The Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance reported in June 2020 that more than 150 regional and community newspapers had ceased printing across Australia due to impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic, “on top of the 106 local and regional papers that closed over the previous decade”.13

“The situation with social media was made worse because we had no local papers to report on what was going on and to keep things honest.”

– Former councillor who did not stand for re-election

The traditional media in the form of regional and community newspapers, and radio stations in many areas, have often played a key role in council elections. These outlets would profile local candidates, feature campaign advertising and umpire political debate between candidates and the community they serve.

Traditional media outlets are bound by defamation laws and a journalism code of ethics, while social media is much less restricted. The closure of so many media outlets in Victoria meant that many communities and candidates lost an ‘independent umpire’ in the run up to elections. Although some community members chose to set up Facebook groups to provide comment on local news, there is no doubt that communities suffered from the loss of qualified and experienced journalists in the 2020 election period.

“During the election, the local media were sent letters with false information about me but the journalists would know it wasn’t true and would call me to let me know they had received them.”

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

We received 45 formal media enquiries (those which required a response to be published in some format) and many more contacts from journalists over the election period. This was similar to the 2016 election period but there was a narrower field of outlets sending through enquiries in 2020.

In the 2012 and 2016 local government elections, we were required to provide warnings to newspapers that printed campaign advertising or ran commentary that breached electoral rules. While we did not issue any warnings in 2020, we issued advice to a regional newspaper that ran an incorrect image of a person putting a cross on a voting paper, which the relevant newspaper promised to remove to avoid voter confusion. Complaints about material in print or online media outlets were also lower than in previous years, which may be linked to the closure of local media and the shift of political debate onto social media platforms.

13. Sourced from MEAA website https://www.meaa.org/campaigns/our-stories/

Social media

“I don’t think social media had a great effect; it is overrated as a tool but I know others would disagree with me.”

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

Social media is popular as a cheap and easy way to broadcast campaign messaging. Increasingly, the public turns to social media as a ‘source of truth’ for news and information about politics.

Policing social media is problematic as the technology companies that run the platforms are based overseas and, until recent times, not subject to many Australian laws on content or publication of material. They have, so far, successfully argued that they are not publishers and therefore are not subject to defamation laws.

With the closure of local newspapers, Facebook was more important than ever in the 2020 council elections. Candidates were able to run a free campaign by setting up campaign pages and using existing community forums or they could pay for advertising.

The Australian Local Government Women’s Association (ALGWA) reported that in the campaign, social media advertising ranged from $50 to $7,000.14 Candidates who were more technologically savvy and had bigger advertising budgets had an advantage in targeting voters in their municipality.

“I found Facebook to be mixed. At times, trolls would jump on anything I posted immediately, and I know that there were former councillors who were encouraging the trolls. But at other times I found that if I paid for advertising, then I was able to get my message out and it was a really useful tool.”

– Councillor elected for the first time in 2020

“I was very low key during the election. I didn’t campaign and didn’t do a letterbox drop. The only thing I did was set up a Facebook page and ran a dog as a ‘candidate’. Using humour on social media helped.

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

However, social media creates audience silos where voters may only engage with things they endorse, and the social media algorithms confirm these biases. The result is that the electorate had limited exposure to alternative messaging. It also means politicians can avoid being challenged in a genuine debate.

We observed this behaviour in the 2020 elections with complaints about candidates blocking their opposition or deleting critical comments to curate their pages and present themselves in a better light.

Social media has proven difficult to regulate and moderate. It can also allow misinformation and disinformation to spread. This can be in the form of an individual posting wrong information or a coordinated political campaign. In addition, the truth can be manipulated by people who are able to remain anonymous.

During the 2020 council elections, ALGWA reported that there was evidence of ‘brigading’, where a group of people with dubious or fake profiles attacked candidates with negative, often intimidating comments in unison or as a group.

Another feature of the 2020 council elections was the use of ‘community pages’ or ‘community groups’ which post information about local issues and have community members acting as volunteer ‘administrators’ or ‘moderators’. These community groups on Facebook have hundreds or thousands of members and it is up to the administrator to remove comments or ban people who do not abide by the rules of the group. These groups do not have any oversight in the same way as traditional publishers, such as newspapers. ALGWA reported that during the 2020 elections, some administrators did not comply with their own group rules and shut down debate which they did not agree with. ALGWA also observed that a candidate that was an administrator for a group with thousands of members transferred the administration of the group to a family member during the election period and did not disclose a conflict of interest. ALGWA said critics have no ability to address or refute misinformation in these groups and voters can be easily misinformed.

In 2020, we received 351 allegations relating to online content, with 75 per cent of these allegations relating to social media, 10 per cent about email, 11 per cent about websites and 4 per cent not specified.

On 9 October 2020, we published a guide, with input from the VEC, detailing the appropriate method of ensuring social media posts are transparent and their author is clearly stated.

“It was virulent. Some of the stuff was atrocious. The problem is that Facebook is utterly unanswerable. You can request material be removed but they don’t take things down and people believe it.”

– Former councillor who did not stand for re-election

“My main opponent blocked comments on Facebook and deleted [negative] comments to make his feed look better. How can you oppose that? I took a different approach. I responded or acknowledged 95 per cent comments I received.”

– Councillor elected for the first time in 2020

We received 266 complaints from across the state related to candidates, ratepayer groups or supporters using social media to post about elections. This compares to the election period in 2016 when 78 complaints were lodged. Most of the complaints have involved potential breaches by candidates of rules around correct authorisation of social media posts or accounts.

As the newsrooms for local newspapers have closed, Facebook community groups run by administrators have sprung up to fill the void. Many complaints were made by candidates or their supporters against community group Facebook pages.

Recently, similar issues have been raised at the federal level and the Australian Electoral Commission has investigated the issue of community and news groups, their lack of transparency and the potential for political figures to misinform the electorate.

We received 38 complaints about commentary included on a website (excluding social media) and 34 related to email content sent by a candidate or authorised person.

“Social media didn’t have an impact on the number of women being elected but it did have a health and wellbeing impact on those that were being attacked. If you have just come out of a brutal election campaign then it doesn’t set you up very well for your new role in council.

“The keyboard warriors had an enormous advantage in 2020. If they were established on social media, then they had a huge advantage over those who were not as good or experienced using social media.”

– Former councillor who did not stand for re-election in 2020

14. Australian Local Government Women’s Association (Victorian Branch) submission to the Victorian Parliamentary Inquiry into the Impact of Social Media on Elections and Election Administration, 9 November 2020.

Case study

Campaign donation returns

“There are only a handful of members of our ratepayers association. It is a fringe group. The ratepayers association funded the campaigns of six candidates but only one candidate declared it.”

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

A campaign donation return is a record of gifts, donations or in-kind support worth $500 or more received by election candidates for use in their campaigns. If candidates did not receive any donations or support, they must still complete and send a return, noting ‘No disclosable gifts’, to the CEO of the council where they are standing for election within a strict time.

Under section 306 of the Act, a candidate must give an election campaign donation return to the CEO within 40 days after election day.16 The return must be in a prescribed form and must detail any gifts worth $500 or more received by or on behalf of the candidate during the donation period. However, this does not include gifts for personal use or not used for election purposes.

Section 307 requires a council CEO to submit a report to the Local Government Minister stating the names of candidates in the election and the names of candidates who submitted a return under section 306 within 14 days after the period specified in section 306(1).17

A council CEO must also ensure that a summary of each election campaign donation return is published on the council’s website.

The purpose of these sections is to ensure ongoing integrity and transparency in the sector. The transparent disclosure of campaign donation returns by all candidates during the election period is fundamental to maintaining the integrity, of not just the elections but more importantly, the future decision-making and governance of councils.

“They need to fix the donation system. It is a system which is based on honesty and if people aren’t honest, that is where it ends. Candidates could have to submit a statement of what they spend on and where they spent it. At least there would be some rigor in the system.

“There is a loophole in campaign donations. Councillors should have to complete the circle, not just have what they say taken at face value.”

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

In 2016, the CEO written donation reports showed that 288 candidates, more than 13 per cent of all candidates, failed to submit their returns to the CEO by the 1 December 2016 due date and 40 of the 288 did so after the deadline.

After the 2016 election period, 15 candidates who were unable to provide a valid reason for non-submission were prosecuted. After receiving a complaint about two more candidates and assessing information in their returns, those candidates were prosecuted or false or misleading information with one receiving a 12-month good behaviour bond and the other case withdrawn.

In 2020, 2,042 candidates handed in a compliant return and 144 were considered non-complaint, a non-compliance of 6.6 per cent. This was almost half the non-compliance rate for the 2016 election period.

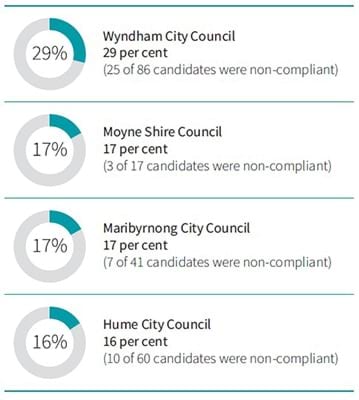

In 2020, the highest percentages of non-compliance came from four council areas:

The highest numbers of non-complying candidates were:

There were four candidates who did not submit a campaign donation return in 2020 or in 2016.

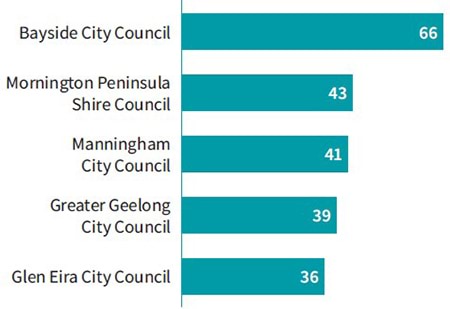

On a positive note, all candidates in 37 council areas submitted campaign donation returns. In addition, the following councils had high numbers of candidates who correctly all submitted campaign donation returns:

16. Section 306 is listed in full in Appendix 2.

17. Section 307 is listed in full in Appendix 2.

Proposed legislative reform

Management of campaign donation returns

In 2020, the new Act was passed. It was the largest reform of the laws governing local government in three decades. The Local Government Bill 2019 (Bill) which was initially drafted included a proposal to increase the responsibilities of the Chief Municipal Inspector (CMI) in relation to campaign donation returns. The proposal would have seen the CMI publish a summary of the gifts recorded in an election donation report within two days of it being lodged. The summary would have included the name of the candidate, name of the donor and the value and nature of the gift.

The immediacy of this proposal would have heightened transparency in local government and the election process. It also received strong support from the local government sector. However, the proposal set out in section 338 of the Bill was not passed by the Victorian Parliament and did not become law.18

It is our belief that the section needs to be included in the Act to increase the transparency and integrity of political donations in local government elections and this will increase public trust in the process.

Recommendations

The Act should be amended to include language consistent with clause 338 of the Local Government Bill 2019 to streamline the submission of campaign donation returns and improve transparency.

The Local Government Inspectorate should be resourced to adequately manage and scrutinise the campaign donation returns process.

Infringements

Part 8 of the Act includes a number of offences relating to the conduct of elections, including matters relating to the authorisation, publication and distribution of election material (sections 287, 289, 290, 291 of the Act), as well as offences related to the requirement to submit campaign donation returns (section 306). These are aimed primarily at ensuring that local government elections are conducted in accordance with the legislation and as transparently as possible.

These offences are relatively minor and most carry relatively low financial penalties. Apart from a potential jail term of six months for offences under section 291, they do not carry the possibility of imprisonment. They are ‘strict liability’ offences; that is, a candidate does not have to intend to commit these offences in order to be guilty; it is only necessary to prove that the accused engaged in the proscribed activity.

Our experience under the equivalent provisions in the 1989 Act indicates that the use of the criminal justice system is a particularly blunt instrument for ensuring compliance with these regulatory provisions. The cost and delay in conducting prosecutions in the court system are disproportionate to the nature and seriousness of the offences.

In addition, we consider that the criminal justice system does not provide an adequate deterrent for candidates who breach their statutory obligations under Part 8 of the Act (either carelessly or deliberately) and that there is a pressing need to amend the Act to allow the CMI to issue infringement notices to persons believed to have committed these offences.

We have previously presented these proposed amendments to the Department of Justice and Community Safety.

Recommendation

The Act should be amended to give the CMI specific power to issue infringement notices.

18. The full clause 338 is listed in Appendix 2.

Conclusion

The 2020 local government elections saw the highest average voter turn-out and were considered a ‘win for democracy’. However, they also saw the highest number of complaints. We received 848 complaints, more than double the number of complaints in 2016. We saw complaints in relation to social media triple.

We are Victoria’s lead integrity agency for councils but work with other agencies to monitor local government elections. Our work would not be possible without the assistance of the VEC, Victorian Ombudsman, IBAC and the Victorian Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission. Due to the restrictions on movement as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, we also worked with Victoria Police.

We are also thankful for the assistance and support of councils for sharing information and working with us to refer information. We also had support from the local government sector and a number of ‘election watchers’ who suppled information and supporting evidence for their complaints.

Our analysis of the data and trends of complaints related to the 2020 elections lead us to propose a number of recommendations to improve the transparency and democracy of Victoria’s local government elections. These recommendations are:

- Councils must be allowed to publicly correct misinformation spread by candidates. To ensure this, Section 69 of the Act must be amended to require councils to adopt an election period policy based on the model election period policy prepared by LGV, which also incorporates flexible election period policies and allows for misinformation to be corrected.

- The eligibility of candidates must be checked at the time of nomination to ensure robust processes are in place to prevent people who have criminal records or have been declared bankrupt running for public office. As such, regulation 24 of the Local Government (Electoral) Regulations 2020 should be amended to require candidates provide a financials records check providing proof of no current or past bankruptcies, a police clearance certificate and a 100-point identification check when nominating for election.

- We must work with the VEC to provide candidates and the community simple and helpful guidance and education on: the rules candidates need to follow

- election material should be authorised

- constitutes a misleading or deceptive matter

- role in electoral matters.

- To help regulate the use of social media in elections, we recommend the amendment of:

- Section 3(1), defining electoral material, and

- Section 287 Printing and publication of electoral material to encompass social media and other forms of electronic communication.

- The IBAC investigation into City of Casey has highlighted the need for integrity and transparency in relation to campaign donations. We recommend the Act be amended to include language consistent with clause 338 of the Local Government Bill to streamline the submission of campaign donation returns and improve transparency.

- As the main local government integrity agency, we should be resourced to adequately manage and scrutinise the campaign donation returns process.

- That the Act be amended to give the CMI specific power to issue infringement notices and that regulations be made prescribing offences and penalties in order to deter offenders and reduce the cost to the taxpayer of pursuing minor offences through the court system.

When compiling the information needed for this report, we were concerned about a number of trends, including bullying and harassment. A number of councillors interviewed for this report raised concerns about social media and the way it easily enables bullying and harassment during the campaign period. They feared that the poor behaviour seen during the 2020 elections will deter quality candidates in the future.

However, some councillors we spoke to also believed that the public were able to see through this behaviour and voted for good candidates regardless of negative and toxic campaigning. We hope the recommendations in this report are acted on in order to ensure a fairer democratic process in the next local government elections. We will continue work with other government agencies to monitor trends in local government elections and help ensure a fair and democratic election process.

Recommendations - 2020 election report

Recommendations

- Section 69 of Local Government Act 2020 should be amended to require councils to adopt a caretaker or election period policy, which: is based on the model election period policy prepared by Local Government Victoria, and incorporates flexible election period policies which allows for misinformation to be corrected.

- Regulation 24 of the Local Government (Electoral) Regulations be amended to require candidates to provide a financial records check providing proof of no current or past bankruptcies, a police clearance certificate and a 100-point identification check when nominating for election.

- The Local Government Inspectorate consult with the VEC and have input into the electoral candidate handbook to ensure candidates receive simple information about the rules and laws candidates need to follow; how election material should be authorised; what constitutes misleading and deceptive matter; and the Inspectorate’s role in electoral matters.

- Updating of the definition of ‘electoral material’ in section 3(1) to encompass social media and other forms of electronic communication.

- Section 287 of the Act should be amended to incorporate social media and other forms of electronic communication.

- The Act should be amended to include clause 338 of the Local Government Bill 2019 to streamline the submission of campaign donation returns and improve transparency.

- The Local Government Inspectorate should be resourced to adequately manage and scrutinise the campaign donation returns process.

- The Act should be amended to give the Chief Municipal Inspector specific power to issue infringement notices.

Appendix 1

Provisions of Acts and Regulations relating to key election complaint themes

Local Government Act 2020

Section 3(1)

electoral material means an advertisement, handbill, pamphlet or notice that contains electoral matter, but does not include an advertisement in a newspaper that is only announcing the holding of a meeting

Section 3(4)

In this Act, electoral matter means matter which is intended or likely to affect voting in an election, but does not include any electoral material produced by or on behalf of the election manager for the purposes of conducting an election.

Section 3(5)

Without limiting the generality of the definition of electoral matter, matter is to be taken to be intended or likely to affect voting in an election if it contains an express or implicit reference to, or comment on—

(a) the election; or

(b) a candidate in the election; or

(c) an issue submitted to, or otherwise before, the voters in connection with the election.

Section 286 Nomination offence

A person who is not entitled to nominate as a candidate for election under section 256 of the Act must not nominate as a candidate for an election.

PENALTY: 240 penalty units or imprisonment for two years.

Section 287 Printing and publication of electoral material

(1) A person must not print, publish or distribute or cause, permit or authorise to be printed, published or distributed, electoral material unless the name and address of the person who authorised the electoral material is clearly displayed on its face.

PENALTY: In the case of a natural person, 10 penalty units; in the case of a body corporate, 50 penalty units.

Section 288 Misleading or deceptive matter

(1) A person must not— (a) print, publish or distribute; or

(b) cause to be printed, published or distributed—

any matter or thing that the person knows, or should reasonably be expected to know, is likely to mislead or deceive a voter in relation to the casting of the vote of the voter.19

PENALTY: 60 penalty units or imprisonment for six months if the offender is a natural person or 300 penalty units if the offender is a body corporate.

Section 293 False or misleading information

(1) A person must not make a statement knowing that it is false or misleading in a material particular in any information provided orally or in writing in relation to voter enrolment or in any declaration or application in relation to an election under this Act or the regulations.

PENALTY: 600 penalty units or imprisonment for five years.

Section 294 Voting offences

(1) a person must not— (a) forge any ballot-paper, prescribed form or other form or document submitted or lodged in connection with an election; or

(b) utter any forged ballot-paper, prescribed form or other form or document submitted or lodged in connection with an election; or

(c) forge the signature of any person on any ballot-paper, prescribed form or other form or document submitted or lodged in connection with an election.

PENALTY: 600 penalty units or imprisonment for five years.

(3) A person must not in respect of an election in respect to an election—

(a) vote in the name of another person, including a dead or fictitious person; or

(b) vote more than once; or

(c) apply for a ballot-paper in the name of another person.

PENALTY: 600 penalty units or imprisonment for five years.

Section 299 Offence to interfere with postal ballot materials

(1) A person must not interfere with any material being, or to be, sent or delivered to a voter by the VEC at an election.

PENALTY: 600 penalty units or imprisonment for five years.

Section 300 Bribery, treating and undue influence

(2) A person must not— (a) ask for, receive or obtain; or

(b) offer to ask for, receive or obtain; or

(c) agree to ask for, receive or obtain—

any property or benefit of any kind for themselves or any other person, on an understanding that the person’s election conduct will in any manner be influenced or affected.

PENALTY: 600 penalty units or imprisonment for five years.

(4) A person must not, in order to influence or affect a person’s election conduct—

(a) give or confer; or

(b) promise to give or confer; or

(c) offer to give or confer—

any property or benefit of any kind to that other person or to a third person.

PENALTY: 600 penalty units or imprisonment for five years.

Section 301 Interference with political liberty

(1) A person must not hinder or interfere with the free exercise or performance by any other person of any political right or duty that is relevant to an election Act.

PENALTY: 600 penalty units or imprisonment for five years.

Section 304 Prohibition on councillors and council staff

(1) A Councillor or a member of council staff must not use Council resources in a way that— (a) is intended to; or

(b) is likely to—

affect the result of an election under this Act.

PENALTY: 60 penalty units.

(2) A Councilllor or a member of Council staff must not use Council resources to intentionally or recklessly print, publish or distribute or cause, permit or authorise to be printed, published or distributed any electoral material during the election period on behalf of, or purporting to be on behalf of, the Council unless the electoral material only contains information about the election process or is otherwise required in accordance with, or under, any Act or regulation.

PENALTY: 60 penalty units.

19. The terms ‘misleading’ and ‘deceptive’ in this context have been narrowly defined by the courts to refer to the effect and understanding of a voter’s vote rather than the decisions made by the voter as to how they will vote.

Appendix 2

Provisions of Act and Bill relating to campaign donation returns

Local Government Act 2020

306 Return by candidate

(1) Within 40 days after election day, a person who was a candidate in the election must give an election campaign donation return to the Chief Executive Officer.

(2) An election campaign donation return must— (a) be in the prescribed form; and

(b) contain the prescribed details in respect of any gifts received during the donation period by or on behalf of the candidate, to be used for or in connection with the election campaign, the amount or value of which is equal to or exceeds the gift disclosure threshold.

(3) Despite subsection (2), a candidate is not required to specify the prescribed details of an amount in a return if—

(a) the amount was a gift made in a private capacity to the candidate for the candidate’s personal use; and

(b) the candidate has not used, and will not use, the gift solely or substantially for a purpose related to the election.

(4) A reference in subsection (2) to a gift made by a person includes a reference to a gift made on behalf of the members of an unincorporated association.

(5) For the purposes of this section, 2 or more gifts made by the same person to or for the benefit of a candidate are to be taken to be one donation.

(6) A person who—

(a) fails to give a return that the person is required to give under this section; or

(b) gives a return that contains particulars that the person knows are false or misleading in a material particular; or

(c) provides information that the person knows is false or misleading in a material particular to a person required to give a return under this section— is guilty of an offence and liable to a fine not exceeding 60 penalty units.

(7) If a person is found guilty or convicted of an offence under subsection (6), a court may make an order that the offender give a return under subsection (1) that is not false or misleading in a material particular.

307 Responsibilities of Chief Executive Officer

(1) The Chief Executive Officer must, within 14 days after the period specified in section 306(1), submit a written report to the Minister specifying—

(a) the names of the candidates in the election; and

(b) the names of the candidates who submitted a return under section 306.

(2) The Chief Executive Officer must ensure that, within 14 days after the period specified in section 306(1), a summary of each election campaign donation return given to the Chief Executive Officer under section 306 is made available on the Council’s Internet site.

(3) If an election campaign donation return is given after the end of the period specified in section 306(1), the Chief Executive Officer must ensure that a summary of the return is made available on the Council’s Internet site.

Local Government Bill 2019

338 Responsibilities of Chief Municipal Inspector

(1) The Chief Municipal Inspector must publish a summary of the gifts recorded in an election campaign donation return lodged under section 335 on the Internet site of the Chief 5 Municipal Inspector within 2 working days of the election campaign donation return being lodged.

(2) The summary of an election campaign donation return must include the following information— (a) the name of the candidate;

(b) the name of the donor;

(c) the value and nature of each gift disclosed.