- Date:

- 23 June 2021

Introduction

Once every four years, Victoria holds its general council elections.

This is generally a vibrant time for local government in Victoria but the pandemic and the resulting restrictions on movement created unprecedented conditions.

The Local Government Inspectorate is the lead integrity agency for Victorian local government.

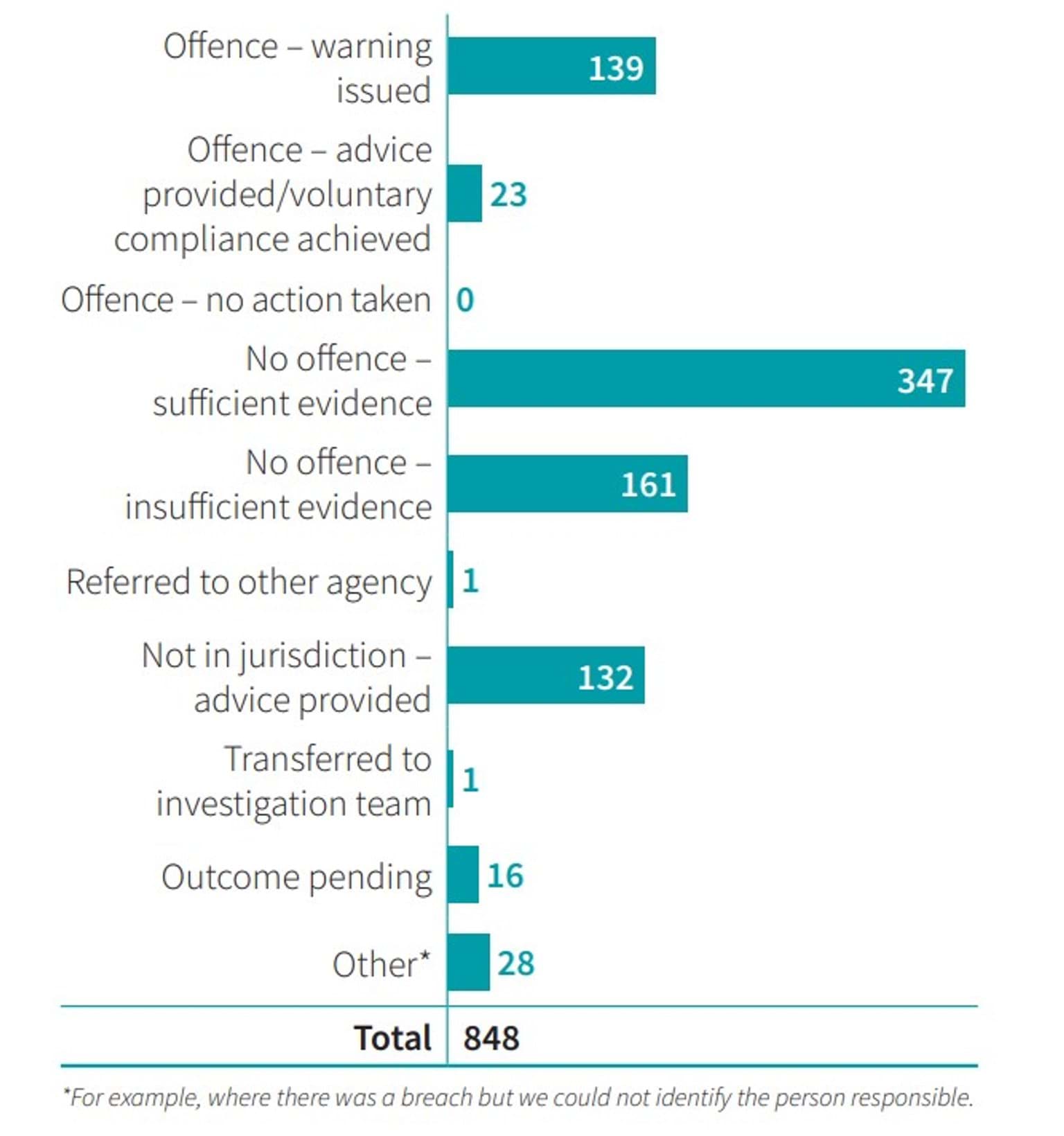

We spoke to long-serving councillors who said the 2020 election was the most vindictive and vitriolic election they had participated in. We saw a 107 per cent rise in the number of complaints – 409 in 2016 to 848 in 2020.

We also saw a 241 per cent increase in social media complaints (from 78 to 266) and a rise in the number of candidates lodging complaints against each other, with some ’weaponising’ our complaints process.

We work with other government agencies to help ensure a fair and democratic election process.

We:

- monitor candidate eligibility

- provide advice to and monitoring the conduct of councils and candidates

- receive and assess allegations

- conduct investigations into potential offences under the Local Government Act (1989 and 2020 Acts).

We work with other integrity agencies to monitor local government elections and are able to receive or refer complaints to other agencies, including the Victorian Electoral Commission, the Victorian Ombudsman and the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission.

Pre-election work - what we achieved

We developed an online election complaint form in August 2020 with comprehensive user testing and plain English wording to ensure complainants could understand what we could and could not receive complaints about.

There were 381 complaints or enquiries lodged through the specific election complaint form during the election period. Other complaints were lodged through the standard online complaint form, phone and email.

Election period policies

All Victorian councils must have a policy covering the election period, also known as the ‘caretaker period’. The election period policies ensure councils are transparent and accountable during the election process. Our website contains some best-practice examples of election period policies from a range of councils.

Candidate eligibility

The current electoral system relies on councillor candidates understanding the eligibility criteria and then correctly completing the nomination form. It is vulnerable to candidates misunderstanding the criteria or having an intention to deceive.

Candidate eligibility needs to be tightened by asking a candidate when they nominate for election to produce a police and bankruptcy check. There is little risk that an eligible and genuine candidate would be prevented from nominating if this requirement was in place.

Candidate booklet

The Victorian Electoral Commission (VEC) produces a handbook for candidates who intend to stand which covers nominating, election campaign material and election compliance. There have been considerable efforts by the VEC to explain the election process simply but there is still room for improvement. We spoke to many candidates who had either not read or had not retained information from the candidate booklet.

Candidates come from a range of backgrounds, including different levels of education, community engagement and different cultural backgrounds. The language and design of the booklet needs to be made as accessible as possible.

Candidate and campaigner behaviour

Robust public debate is an accepted part of all levels of politics. While candidates must accept a certain level of questions and criticism during their campaign, there have been reported instances where candidates have been harassed online, followed or received death threats.

A lot of the complaints we received were driven by a misunderstanding of the definition of ‘misleading and deceptive behaviour’. During a political debate, candidates can speak freely but unethical behaviour is not necessarily illegal.

Many complaints focused on allegations of a breach of section 287 Printing and publication of electoral material with the majority related to material published online. Because the wording in the Act does not specifically mention online or social media material, we joined the VEC in publishing information in the lead up to the election to advise candidates on the correct methods for authorising campaign material on social media.

Sexism, harassment, bullying and social media

Sexism, harassment and bullying were again featured in the 2020 local government election period. Although we are not the primary body that would receive serious or criminal complaints of this nature, we received 18 election complaints that mentioned harassment, threats or intimidation in 2020. A further 25 complaints mentioned defamation.

We observed examples of social media-based harassment and bullying by people posting anonymously or using fake accounts. Comments in a closed Facebook group set up to advance female representation in Victorian councils, ‘More women for local government’, indicated that women candidates bear the brunt of bad behaviour.

Role of media in elections

Traditional media

Traditional media outlets are bound by defamation laws and a journalism code of ethics. The closure of many media outlets in Victoria in 2020 meant that many communities and candidates lost an ‘independent umpire’ in the run up to elections. Although some community members chose to set up Facebook groups to provide comment on local news, many communities suffered from the loss of qualified and experienced journalists in the 2020 election period.

Social media

In 2020, we received 351 allegations relating to online content, with 75 per cent of these allegations relating to social media, 10 per cent about email, 11 per cent about websites and 4 per cent not specified.

We received 266 related to social media. Most of the complaints have involved potential breaches by candidates of rules around correct authorisation of social media posts or accounts.

Facebook was more important than ever in the 2020 council elections. Candidates were able to run a free campaign by setting up campaign pages and using existing community forums or they could pay for advertising.

However, social media creates audience silos where voters may only engage with things they endorse, and the social media algorithms confirm these biases. Consequently, the electorate had limited exposure to alternative messaging and candidates could avoid being challenged in a genuine debate.

Social media was difficult to regulate and moderate. It can allow misinformation and disinformation to spread. This can be in the form of an individual posting wrong information or a coordinated political campaign. In addition, the truth can be manipulated by people who are able to remain anonymous.

Another feature of the 2020 council elections was the use of ‘community pages’ or ‘community groups’, where members post information about local issues. Candidates, residents and supporters posted in those pages and groups about election issues and some posts – often that disparaged candidates or other group members on election-related topics – were the topic of complaints to our office.

Campaign donation returns

A campaign donation return is a record of gifts, donations or in-kind support worth $500 or more received by election candidates for use in their campaigns.

Section 307 requires a council CEO to submit a report to the Local Government Minister stating the names of candidates in the election and the names of candidates who submitted a return under section 306 within 14 days after the period specified in section 306(1).

A council CEO must also ensure that a summary of each election campaign donation return is published on the council’s website.

The transparent disclosure of campaign donation returns by all candidates during the election period is fundamental to maintaining the integrity, of not just the elections but more importantly, the future decision-making and governance of councils.

In 2020, 2,042 candidates handed in a compliant return and 144 were considered non-complaint, a non-compliance rate of 6.6 per cent. This was almost half the non-compliance rate for the 2016 election period.

In 2020, the highest percentages of non-compliance came from four council areas: Wyndham City Council (29 per cent), Moyne Shire Council (17 per cent), Maribyrnong City Council (17 per cent), and Hume City Council (16 per cent). There were four candidates who did not submit a campaign donation return in 2020 or in 2016.

On a positive note, all candidates in 37 council areas submitted campaign donation returns. At Bayside City Council, all 66 candidates submitted returns.

Proposed legislative reform

Management of campaign donation returns

The Local Government Bill 2019 (Bill) included a proposal to increase the responsibilities of the Chief Municipal Inspector in relation to campaign donation returns. The proposal would have seen the Chief Municipal Officer publish a summary of the gifts recorded in an election donation report within two days of it being lodged. The summary would have included the name of the candidate, name of the donor and the value and nature of the gift.

The immediacy of this proposal would have heightened transparency in local government and the election process. It also received strong support from the local government sector. However, the proposal set out in section 338 of the Bill was not passed by the Victorian Parliament and did not become law.

It is our belief that language consistent with section 338 should be included in the Act to increase the transparency and integrity of political donations in local government elections and this will increase public trust in the process.

Infringements

Part 8 of the Act includes a number of offences relating to the conduct of elections. These offences are relatively minor and most carry relatively low financial penalties.

Our experience under the equivalent provisions in the 1989 Act indicates that the criminal justice system, namely the cost and delay in conducting prosecutions in the court system, is disproportionate to the nature and seriousness of the offences.

We also consider that the criminal justice system does not provide an adequate deterrent for candidates who breach their statutory obligations under Part 8 of the Act and that the Chief Municipal Officer should be able to issue infringement notices to persons believed to have committed these offences.

We have previously presented these proposed amendments to the Department of Justice and Community Safety.

Conclusion: 2020 council elections report

Our work monitoring local government elections would be a more difficult task without the assistance of the VEC, Victorian Ombudsman, IBAC and the Victorian Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission. We are also thankful for the assistance and support of councils for sharing information and working with us to refer information.

We were concerned about a number of election trends, including bullying and harassment. A number of councillors interviewed for this report raised concerns that this behaviour would deter quality candidates in the future. However, some councillors we spoke to also believed that the public were able to see through this behaviour and voted for good candidates regardless of negative and toxic campaigning.

We hope the recommendations in this report are acted on in order to ensure a fairer democratic process in the next local government elections. We will continue to work with other government agencies to monitor trends in local government elections and help ensure a fair and democratic election process.

Recommendations

1. Section 69 of Local Government Act should be amended to require councils to adopt a caretaker or election period policy, which:

- is based on the model election period policy prepared by Local Government Victoria

- incorporates flexible election period policies which allows for misinformation to be corrected.

2. Regulation 24 of the Local Government (Electoral) Regulations be amended to require candidates to provide a financial records check providing proof of no current or past bankruptcies, a police clearance certificate and a 100-point identification check when nominating for election.

3. The Local Government Inspectorate consult with the VEC and have input into the electoral candidate handbook to ensure candidates receive simple information about:

- the rules and laws candidates need to follow

- how election material should be authorised

- what constitutes misleading and deceptive matter

- the Inspectorate’s role in electoral matters.

4. Updating of the definition of ‘electoral material’ in section 3(1) to encompass social media and other forms of electronic communication.

5. Section 287 of the Act should be amended to incorporate social media and other forms of electronic communication.

6. The Act should be amended to include clause 338 of the Local Government Bill 2019 to streamline the submission of campaign donation returns and improve transparency.

7. The Local Government Inspectorate should be resourced to adequately manage and scrutinise the campaign donation returns process.

8. The Act should be amended to give the Chief Municipal Inspector specific power to issue infringement notices.

Election complaints data and themes

During the 2020 election period, we received 848 complaints; this compares with an average of 500 complaints a year in a non-election year. During the 31 days of the election period, our staff handled an average of 36 complaints per day.

Those who contacted us for guidance, information or to lodge a complaint included councils, councillors, candidates and voters.

Where we received complaints from

Of Victoria’s 79 councils, we received no complaints about 20 councils (including three under administration where there were no elections) and received 10 or less complaints per council about 37 councils. This meant the vast majority of complaints (78 per cent) related to just 22 councils. Furthermore, 228 complaints – a quarter of all complaints – related to just three councils: Nillumbik, Stonnington and Wyndham.

Who were the complaints from and who were they about?

The majority of complaints were made by members of the public (40 per cent) with the second-highest number coming from candidates, including councillors standing for re-election (38 per cent). About 13 per cent were anonymous. Most complaints were about candidates (53 per cent), followed by complaints about councillors running for re-election (23 per cent).

Breaches and offences against the Act

When assessing complaints, we look at whether or not there has been a breach or offence against the Local Government Act and what section of the Act has been breached.

| Section | Number of complaints |

|---|---|

| 288 Misleading and deceptive matter | 263 |

| 287 Printing and publication of electoral material | 244 |

| Not applicable* | 172 |

| 286 Nomination offence** | 54 |

| 300 Bribery, treating and undue influence | 33 |

| 304 Prohibition on councillor or member of Council staff | 33 |

| 76D Misuse of position | 19 |

| 252 Provision of voter’s roll to candidate | 9 |

| 299 Offence to interfere with postal ballot materials | 9 |

| 289 Heading to electoral advertisements | 3 |

| 294 Voting offences (includes forgery) | 3 |

| 301 Interference with political liberty | 3 |

| 290 Author to be identified | 2 |

| 293 False or misleading information or particulars | 1 |

* Includes complaints about COVID-19 restrictions, defamation, intimidation and placing or removing posters without permission.

** Includes dummy candidates (26 complaints) and eligibility due to residence, character, alleged criminal history or conflicting duties (23 complaints).

Rise of social media complaints

In 2020, complaints about the use of social media and online content in election campaigns more than tripled, from 78 in 2016 to 266 in last year.

We received an increase of 118 per cent of complaints about the authorisation of election material during the 2020 election period and 31 per cent of all issues raised were about content that was specifically published online.

While social media provides an economical way for candidates with limited financial backing to reach the electorate, it can produce challenges for existing legislation.